I shall astonish Paris with an apple.

—Paul Cézanne2

1

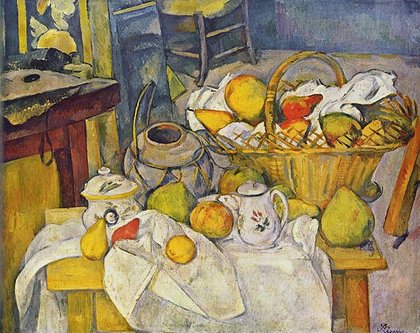

In still lifes Time comes to a stop; we might better call them dead stills (the phrase for still life in French is, after all, Nature morte). All still lifes represent the experience of Time, but turned around. In reality, life rushes past us, through us, propelling us to the end, to the stillness, to death. Our lives are like the fruit in Sam Taylor-Johnson’s Still Life, where a bowl of fresh peaches, pears, and grapes decays, in a time-lapse video, down to a giant petri dish of collapsing green, gray, and furry mold.3 In Cézanne’s picture Time stands still, has stood still, for more than a century. If we could stop Time, we would also stop dead, like the fruit in Cézanne’s painting.

the table’s surface

if viewed at the speed of light

is an illusion

of substantiality

energy and mass the same

each substantial bit

little more than electrons

whirling in orbit

creating plasma force fields

which make an oak door solid

from the right angle

of vision, even fresh fruit

is always already

decaying; our bodies age

and die while we’re still watching

2

The painting is divided into two spaces or sections; the first and the largest occupies two thirds of the canvas, starting in the lower right corner and moving upwards and out; the second is in the upper left corner, moving downwards. The kitchen table, in the first space, holds fruit, a full basket, a small coffee pot, what looks like a sugar bowl, and a raffia-corded ginger jar, all of which seem perched, ready to tumble off onto the floor, though they cannot. Yet, in the other space, the compteur and its contents, the chair, and the Matisse-like tapestry in the upper left, are secure, their surfaces oblique to the kitchen table’s. This imbalance, this energy in the composition, intensifies the painting’s depiction of stopped Time, and cannot help but illustrate the moving eye.

none would be tempted

to eat this scuffed-up wooden fruit

its dark outlines tell

you this is a picture, not

real pears. Pot and sugar bowl

shrink back from the edge

of the white linen precipice

while a viewer’s gaze runs

here and there on the canvas

trying to see everything

shifting attitudes

mimic Eadweard Muybridge’s

Sallie Gardner at a Gallop

twelve photos as the horse ran by

gave the idea of motion

3

For many years, while our children were growing up, we travelled to France in the summer, renting gîtes (modest furnished country houses), shopping in the local markets, and otherwise living as habitants. Each gîte was different, of course, but they were also very much alike, not least for their old family furnishings. In the kitchens, especially, we would always find things like copper pots and pans, a cracked ceramic pitcher, a bud vase, old mixing bowls, wax fruit, a salt box, a wire basket, espresso pot, a chinois, and a cast-iron cocotte. Sometimes, as we were washing up after supper, we remarked how the drain board looked like a carefully arranged still life. Next day it would be gone.

the urge to preserve

moments monitored by things

recalling the touch

of a fresh peach, an apple

in the shadow of a cup

on television

nothing but French news programs

impenetrable

talent shows, laughing at jokes

we could never understand

a broken croissant

butter and jam on a plate

pitchers of coffee

and hot milk—a rapprochement

worthy of a great painter

is a retired university professor who lives in Northampton, Massachusetts with his

wife, Ann Knickerbocker, an abstract painter. Tarlton has been writing poetry and

flash fiction since 2006, and his work is published in: Abramelin, Atlas Poetica,

Barnwood, Blackbox Manifold, Blue and Yellow Dog, Cricket Online Review, Fiction

International, Haibun Today, Inner Art Journal, Jack Magazine, KYSO Flash, Linden

Avenue Literary Journal, Prune Juice, Rattle, Red Booth Review, Review Americana,

Shampoo, Shot Glass, Simply Haiku, Six Minute Magazine, Sketchbook, Skylark,

Tipton, and Ink, Sweat, and Tears.

He has also published a poetry e-chapbook in the 2River series, entitled La

Vida de Piedra y de Palabra (a free translation of Neruda); a tragic historical

western in poetry and prose, “Five Episodes in the Navajo Degradation,”

in Lacuna; and “The Turn of Art,” a short poetical drama

pitting Picasso against Matisse, composed in verse and prose, which appeared in

Fiction International.

[Tarlton’s ekphrastic tanka prose are featured in

State of the Art, the 2016 KYSO Flash print anthology.

Two others appear in

Issue 8 online. Links to additional ekphrastic works by

Tarlton, and to his essay on ekphrasis and abstract art, are listed below.]

⚡ Featured

Author Charles D. Tarlton, with six of his ekphrastic tanka prose and an

interview with Jack Cooper, in KYSO Flash (Issue 6, Fall 2016)

⚡ Notes for a Theory of Tanka Prose: Ekphrasis and Abstract Art, an essay by

Tarlton residing in PDF at Ray’s Web; originally published in Atlas Poetica (Number 23, pages 87-95)

⚡ Three American Civil War Photographs: Ekphrasis by Tarlton in Review

Americana (Spring 2016)

⚡ Rowing Home, Tarlton’s ekphrastic tanka prose on the watercolor by Winslow Homer, in

Contemporary Haibun Online (January 2018)

⚡ Simple Tanka Prose for the Seasons, a quartet by Tarlton in Rattle

(Issue 47: Tribute to Japanese Forms, Spring 2015)

⚡

La Vida

de Piedra y de Palabra: Improvisations on Pablo Neruda’s Macchu

Picchu, Tarlton’s e-chapbook of a dozen poems, with the author

reading several aloud; chapbook is also available in PDF, with cover art by

Ann Knickerbocker

“the father of modern art,” was born in Aix-en-Provence (aka Aix), France, in 1839 and died in 1906 in the city of his birth. He is considered among the greatest of the Post-Impressionist painters, known especially for his varied painting style. While his art was discredited by the public and panned by critics during most of his life, works from his last three decades influenced the aesthetic development of 20th-century artists such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso.

In 1895, art dealer Ambroise Vollard arranged a show of Cézanne’s works in Paris and promoted them successfully over the next few years. By 1904, Cézanne was featured in a major official exhibition, and by the time of his death two years later he had attained legendary status. His art is now seen as the essential link between the ephemeral aspects of Impressionism and the more materialist movements of Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, and even complete abstraction.

(Sources include biographies of the artist at The Art Story: Modern Art Insight and Paul Cezanne dot org, retrieved 14 August 2018.)