|

KYSO Flash ™

Knock-Your-Socks-Off Art and Literature

|

|

|||

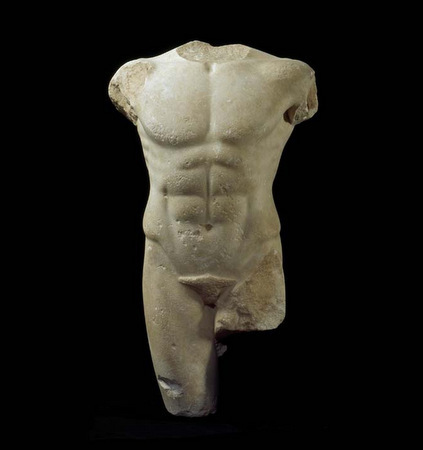

The Miletus Torso *by Charles D. Tarlton

And yet his torso 1 The first things we all notice are the monstrous amputations: there are no arms or hands, no legs or feet, nor any neck or head remaining. From across the room at first, I thought it was an heroic cuirass on display, one of those breast armor pieces of the sort we’re used to seeing on Roman generals and emperors in the movies.

rough, dismembering

hobbling on the stump

motionless ideas 2 Imagine, then, in stone, the fingers of a left hand curled around the cherry-dogwood shaft of a spear, while the right hand holds the rim of the hoplite shield leaning against his right thigh. Alternatively, think of an ancient Corybant, his left external oblique muscle twisting slightly at exactly the moment when his leg poised to step out the driving rhythm of the dance.

whoever the god

the human figure

here we have human 3 The Miletus Torso represents the human figure deconstructed, and we can only speculate as to the process by which arms, legs, and head were broken off and lost. By accident, as it were, we are forced to concentrate on the center and imagine the whole lost figure. Michelangelo’s Atlas Slave** represents the opposite case in which arms, legs, and head are (at least partially) “missing.” But rather than being lost they are blocked forever in an endless process of becoming. The artist has deliberately forced us to create what he has left out. Ironically, then, the same ingenuity is required to understand each of these two works; in the case of the ancient torso we have to visualize something that is missing but has been lost; in the case of the Renaissance slave, we have to visualize what is missing and is yet to be.

unforgiving stones

everything in germ

how just a hammer

Author’s Notes:

Publisher’s Notes:

|

|

Site contains text, proprietary computer code, |

|

| ⚡ Many thanks for taking time to report broken links to: KYSOWebmaster [at] gmail [dot] com ⚡ | |