|

KYSO Flash ™

Knock-Your-Socks-Off Art and Literature

|

|

|||

“Softball-Sized Eyeball Washes Up on Florida Beach”: The Proetic Vision of Kathleen McGookeyby Clare MacQueen

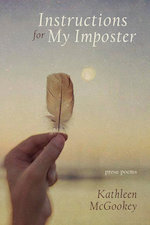

Instructions for My Imposter Poems, prose poems, and translations by Kathleen McGookey have appeared in dozens of literary venues. Both music and magic flare within her writing, sparked in part by paradox, by the inherent tension between two contradictory impulses which complement and complicate one another—the lyric and the narrative. Her latest collection, Instructions for My Imposter, is an irresistible read: 63 resonant and lovingly polished works that sing their stories with only a few well-chosen details and images. As the poet says, in Sandra Arnold’s “Interview with Kathleen McGookey” (New Flash Fiction Review, 2018), “I write a lot about grief and loss and absence.” A few examples include the more philosophical “Change Your Life Through the Power of Math,” in which you can “reduce the ex-boyfriend to an imaginary number,” to the anguish of losing one’s mother to cancer, to the narrator’s “Ultrasound at Fifty” and her heartbreaking “Procedure,” in which “my ghosts peer into a cement leaf,” both of which speak to concerns about her own mortality in turn. The poet also writes about what she calls “surprising daily moments,” poems inspired by family life with children—but she transforms the ordinary into the slightly surreal by incorporating disparate elements from other contexts. In “Star-Crossed,” for instance, as the narrator slept, “Death pinned up linen swatches in my brain. Then he knocked out some walls. New curtains can only do so much. What this place needs, Death said, is a little more light....” And then there’s the charming “Story for Combing Out Lice” with its surprising analogy, and “Little Parenting Assignment #112” in which a dream about a ravenous bear represents a range of ordinary dangers and fears no doubt familiar to many parents. Not to mention, two tiny fairy tales: the chilling “Such Pretty Fish,” which can be seen as a cautionary tale never to leave children unattended at playgrounds, and “Hearing Voices,” an allegory inspired by news stories of human ears grown from stem cells on the backs of living lab rats. In his blurb for an earlier McGookey collection, Stay (Press 53, 2015), Jack Ridl says, “These poems leave us refreshingly off-kilter....” And the same could be said of this collection, Instructions for My Imposter. For example, the poem “X-ray” offers us a slightly different way to see reality, where “skeletons ride the bus to class or work or the flower shop to buy a lavender bouquet.” It’s a bit like looking at the world while hanging upside down from a favorite tree branch. In “Softball-Sized Eyeball Washes Up on Florida Beach” (inspired by an actual headline reported by the Associated Press in October, 2012), scientists work to make sense of a magical, mysterious event: A clear, deep blue, the eyeball was darkest in its center—picture an abyss—and ringed in black. The scientists took turns cradling it in their gloved hands. When night settled over the laboratory, they held it to the window and showed it the moon. Then the scientists flung themselves into their gold filigreed thrones, deeply dismayed. The moon and the eyeball had ignored each other. They wrapped and unwrapped the eyeball in silver heat-reflecting blankets. They tested it for loneliness and ghosts. They weighed it in ounces and grams and calculated its equivalent in vapor. Not all scientists approved of this approach. At the water cooler, a small group grumbled. If someone has something to say, one scientist said in a high, tight voice, I wish she’d just say it. That scientist clicked her pen and clipped it onto her white pocket. Anyone could see this wasn’t a friendly eyeball, yet they still petted its back, where a few stringy muscles dangled, so as not to obscure its view. They rolled it through the maze reserved for rats and recorded its speed. No one was surprised when the eyeball couldn’t find its way back to the start. Every test proved inconclusive. In the end, the scientists settled for sitting in a circle and gazing into its blue-black depths. Even though it felt like drowning, none could look away. The poet draws a connection between being mesmerized by the depths of the eye (“picture an abyss”), that mystery which defies scientific interpretation, and drowning, a metaphor describing the feelings of anxiety and distress that many people associate with uncertainties. Another mystery here, though implied, is the ocean itself, the source of all life. With the eye of an artist, McGookey creates haunting imagery, further exemplified by this trio of examples:

The prose poem is an overnight bag which the writer must pack carefully, given there’s room only for essentials. Most of McGookey’s prose poems run fewer than 200 words. Crucial in micro-works like these are memorable opening and closing sentences, to hook readers and leave them with a haunting image—which McGookey delivers, yet she also pays close attention to all of the words in between. Her prose poems are burnished and buffed until they shimmer with elegance. Gliding along the edges of a lovely strangeness, they’re the perfect melding of narrative and lyric, story and song. * Both prose poems appear here in KF-12: The Waiting and In Paris Clare MacQueenIssue 12, Summer 2019

is founding editor and publisher of the KYSO Flash online literary journal, and served as webmaster and associate editor for Serving House Journal from its inception in January 2010 through its retirement in May 2018, after publishing 18 issues. She is a co-editor of Steve Kowit: This Unspeakably Marvelous Life (Serving House Books, 2015), and the editor, designer, and publisher of 14 books for her KYSO Flash micro-press. She serves on the Senior General Advisory Board for The Best Small Fictions, published by Sonder Press in 2019 (and Braddock Avenue Books in 2018 and 2017). For the 2016 edition, published by Queen’s Ferry Press, she served as Assistant Editor, Domestic. MacQueen’s short fiction, essays, and poetry appear in Firstdraft, Bricolage, New Flash Fiction Review, Serving House Journal, and Skylark, among others; and her essays appear in the anthologies Best New Writing 2007 and Winter Tales II: Women on the Art of Aging. Her nonfiction won an Eric Hoffer Best New Writing Editor’s Choice Award and was nominated twice for a Pushcart Prize. More on the Web: By, About, and Beyond⚡ The Fortune You Seek Lies in a Different Cookie, fiction in New Flash Fiction Review (Issue 10, January 2018) ⚡ Tasting the New, micro-fiction in Serving House Journal (Issue 1, Spring 2010) ⚡ A Visit with the Bee-Headed Monster of the Black Lagoon, an article in Beelines (May 2013, pp. 5–7) based on MacQueen’s phone interview with author and retired English teacher, Terry Johnson, who has kept bees for more than 50 years ⚡ Clan Apis: A “Comic Book” by Jay Hostler, MacQueen’s review of the remarkable, genre-bending, award-winning book in Beelines (July 2013, pg. 8); also appearing on page 8 of that issue, photos of her bees feeding on honey |

|

Site contains text, proprietary computer code, |

|

| ⚡ Many thanks for taking time to report broken links to: KYSOWebmaster [at] gmail [dot] com ⚡ | |